| |

|

| |

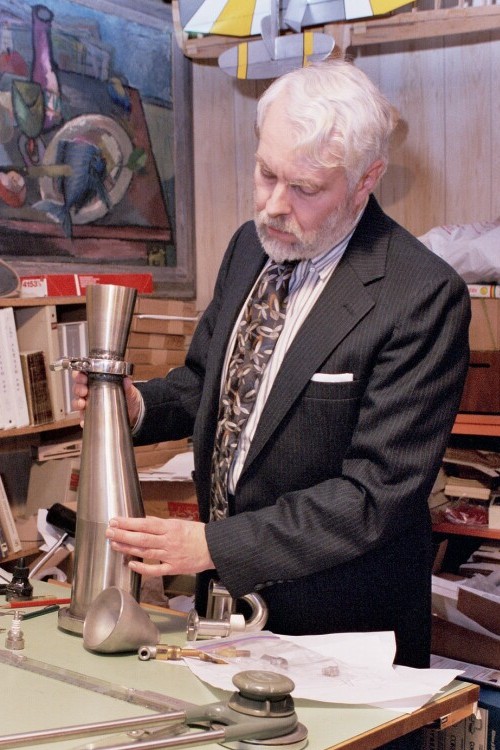

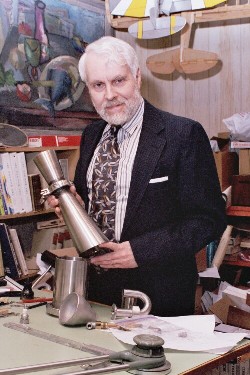

CEO & Director of Product Development Larry Cottrill with Cyclodyne(TM)

engine prototype parts and subassemblies [NOTE: No proprietary or patentable design elements are illustrated in this photo]

Photo Copyright 2003 Cottrill Cyclodyne Corporation |

Q: To you, yourself, what was the personal impact of NASA's

response?

A: In other words, how did it feel to be rejected by NASA? [Laughing]

OK, the first thing to understand is that I was quite realistic

about my chances. I knew it would be an absolute miracle if I

ended up with that grant. The next thing is, this came in on

September 11, 2001 -- the whole office where I work (my "day

job") had just witnessed the tragedies at the World Trade Center

and the Pentagon via CNN; so, probably, some of the disappointment

I would have felt personally was simply dwarfed by the concern

we all felt for the people who had taken such deep losses earlier

that day. So, really, NASA's response wasn't quite the crushing

blow that I had expected to feel. It was disappointing, of course,

like any situation of high hopes that don't pan out -- but it

all seems pretty small when you think about a spouse or dad or

mom who isn't ever coming home again.

Q: But you must have had a lot invested personally -- after all,

this was a one-man corporation at that time!

A: Well, it still is! You have to realize, though, that small

outfits are pretty light on their feet in terms of things like

this. A big company would have spent thousands just preparing

their grant proposal, because of having to pay people. I did

all the research and writing personally, so the cost was

virtually zero. Well, of course, I'm talking about costs in

cash -- I guess you'd have to say that there was an 'opportunity

cost': preparing the proposal was about the only thing I could

manage to do for a couple of months, before the submittal. So

there is always a cost, and that's your risk in going into

something like this. If the grant had happened, it would have

been well worth it, of course. Actually, it WAS well worth it,

anyway -- the lessons learned in the process were invaluable!

Q: Briefly, can you summarize the business impact?

A: Well, I can't summarize ANYTHING 'briefly'-- but, I'll

do the best I can:

First, you have to understand that not much had been invested in

terms of real assets -- just a few hundred dollars for materials

and the time to develop what were basically just schematic

drawings [i.e. usable as 'patent drawings']. Plus, some time and

a little more than $1200 on patent searches. A little welding of

stainless steel parts had been done by me and some fabrication

of other stainless assemblies had been contracted out, but that

just amounted to a few hundred dollars. Since I bore those costs

personally, it seemed like a lot at the time, but it really

didn't amount to much in terms of the whole life of the project.

I mean, I expected for this to become a serious product

development -- revolutionary, and all that. If you want to

change the world, you understand it's going to cost you

something -- the question is whether it's worth going on ahead

at any particular moment, with the resources you have available.

Probably the most serious impact is credibility with potential

investors. It's one thing for friends and co-workers and so on

to say "Wow, that's really exciting!", and quite another thing

for people to risk real money on an unproven idea. It's funny -

if I'd take NASA's response and just edit it down to, you know,

just quoting the positive things NASA said, it would sound like

a fabulous opportunity! But, of course, I won't do it that way

-- I don't think any Christian businessman would do it that way.

You have to take the bitter with the sweet, and you have to be

honest about what you've got to offer, every time down the chute.

That's why I don't have any 'sales pages' for my tiny jet engine

designs; they're just not 'perfected' enough to be good product

offerings - yet. It is frustrating, though, to work without ANY

capitalization -- product development just takes FOREVER, because

you can't just leave your "day job" with its life-sustaining benefit

package behind. So, your time is very, very limited. One of the

reasons I've gotten involved in 'net marketing is to try to

capitalize the business to support further jet engine development

work -- but, that has yet to be really fruitful.

From an investor's standpoint, this has to be regarded as one of

the riskiest things you could get into. Even IF the design works

[which has yet to be proven!], you'd be marketing against some of

the most powerful corporations in the world. Also, think of the

product liability issues -- what will you do the first time a

jetliner crashes with YOUR powerplant aboard, and everybody's

suing everybody? The big players have massive staffs to deal

with inevitable horrors like this. Interesting topics to ponder,

don't you agree?

| |

|

| |

Showing the tail cone subassembly as it would be aligned

with the combustion chamber wall [NOTE: No proprietary or patentable design elements are illustrated in this photo]

Photo Copyright 2003 Cottrill Cyclodyne Corporation |

Q: You don't feel there was any lack of fairness -- like 'prejudice

against the little guy' or whatever?

A: Look at it realistically, from NASA's perspective. They've got just so

much money - federal money - allotted specifically for the purpose

of these grants. Taxpayer's money. Now, what would you do with a

proposal from a guy grinding out drawings in his basement,

welding up stainless in his garage, and telling you he's going to

test in a pit in the backyard with a pair of goggles, hearing

protection, and a couple of fire extinguishers handy? And, this is

an idea that isn't like anything conventional -- any existing

manufacturer would need to heavily re-tool to produce it! And, the

guy doesn't give you the detailed math to prove that it should

work (one of my basic mistakes in the proposal). AND, the guy is

not even an engineer, just a 'lone inventor' working mainly off

of 'inspiration'. Now, 99% of the other proposals are from at

least fairly well-established companies with TEAMS of engineers --

almost always with their own manufacturing facilities already

set up, producing aviation powerplants that other companies are

actually buying! What would you do, if it was your call?

Well ... if the idea was OBVIOUSLY revolutionary, you might give

the 'new kid' a chance, IF it also seemed feasible. NASA didn't

really express any doubt that I knew how to do the work -- the

whole case rests on the uniqueness and the feasibility of the

design. Without some heavy math, feasibility is what's left in

question. And of course, EVERY inventor thinks his latest design is

obviously revolutionary. Maybe NASA didn't think it was (or maybe

just not revolutionary ENOUGH). At least one of the reviewers

said he felt it was basically a good idea, so I have to think the

perceived feasibility of the particulars of this design was really

the main issue.

Q: What would the Phase I Grant have meant, in time and money?

A: Everybody makes their proposal come as close to the $70,000 limit

as possible -- my request total was $69,993.00, and of course, I

was cutting some things to the bone to do that. One tremendous

blessing was the estimate I got from Quality Manufacturing (of

Urbandale, Iowa) for the stainless fabrication of the Production

Prototype, for under $10,000! I was ELATED at that estimate -- that

was for the COMPLETE fabrication of all stainless parts, precision

laser cutting, TIG welding, the whole works! That terrific bid

would have left me with $60,000 for everything else, from finishing

up the Inventor's Concept Model through all the testing and the

inevitable refinements and design changes. I would have been

given six months, while required to work 20 hours/week of MY OWN

time, which would have made it possible [just barely] to keep

my "day job" with benefits [putting in 32 hours per week]. So,

barring any personal disasters such as major illness, it was an

intense but workable schedule.

I'm not sure I'd try to work that same schedule if private money

were involved, but I AM sure the $70,000 would still get the job

done -- in the sense that at the end of that time frame and

expenditure, you would KNOW whether you had something that would

really impact the market! The experimental regimen proposed was

not all that demanding or difficult. One real ADVANTAGE of private

money would be that the NASA SBIR Grants can't be used for any

patent work, nor for tooling up for the project! [One of my biggest

deficiencies is that, admittedly, I don't have an adequate shop --

this makes it tough to make the necessary changes quickly and

cost-effectively.]

Q: So, what do you see for the future of this design?

A: Well, that depends on what happens on the investment side -- if

things stay the way they are, this design will remain on hold.

That doesn't mean other jet engine projects can't move forward. The

tiny pulsejet designs require (or at least, SHOULD require) a

lot less expense and effort, and if I can come up with a really

good one, priced exactly right, the short-term market would be

enormous -- enough to easily capitalize further development of

the Cyclodyne, which was always intended to be the 'bread and

butter' product of the organization.

The only way the Cyclodyne design could take off quickly would

be for someone with risk capital to spend to really get enthused

about the potential for the product, kind of like Harry Guggenheim

got involved with Dr. Robert Goddard and financed a lot of

his rocket experimentation in the desert back in the 1930s.

Charles Lindbergh was also involved in that to some extent, I

think -- at least, I know he visited Dr. Goddard's test site to

observe what was going on. I'd MUCH rather have somebody with a

fired-up imagination than somebody whose only interest is to

make big money. Of course, no one who can't see any commercial

potential in this particular jet engine design is going to

step up anyway. And that's fine. But there must be someone out

there who can see the limitations of current jet engine

technology and the advantages of doing things in a fundamentally

simpler way -- and that's who I'd appeal to, if I just knew an

effective way of doing that. So far, I haven't found it.

I don't need the typical Venture Capitalist who wants to come in,

change everything to his liking, make a quick profit and move on

to his next career project. I need someone genuinely interested in

the long-term technological and commercial impact, who wants to

be in on the genesis of a new way of thinking about jet propulsion.

Someone like that is tough to find. I'm not really sure how much

NASA's opinion would mean to someone like that, if they really

believed in the principle of the design and could be convinced of

its merits. And, convinced that the deficiencies can be overcome,

of course -- no design is perfect. We just need to find the right

man or woman who can study it through and still end up believing

that it can work, technically AND business-wise.

|